THE NEED FOR A NEW DEATH | A blog post

By Elena Freck, Production Dramaturg (Everybody)

What does Death look like, in your mind’s eye? If you grew up in the U.S. or Europe, you’re probably conjuring an image of the Grim Reaper. Tall guy, skull face, black cloak, carrying a scythe—sound familiar? You may also know that our popular conception of Death as a hooded, human-like form emerged during the 14th century, when the original outbreak of the bubonic plague occurred in Europe. The imagery of the Grim Reaper is grounded in that period and place. The black robes mimic the appearance of religious officials during funerary proceedings of the era, and the scythe was a common agricultural tool used to ‘reap’ or harvest crops, hence the association between it and the harvesting of souls from the earth.

In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the Grim Reaper personification has continued to permeate popular culture as one of the most ubiquitous representations of Death. In literature, Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series and Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief famously include the robed reaper. Ingmar Bergman’s 1957 classic The Seventh Seal set the bar for depictions of Death on the big screen, inspiring parodies in later films such as Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey and Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life. The Grim Reaper is also a ubiquitous presence in modern television cartoons. Shows from The Simpsons and Scooby Doo to The Regular Show and The Grim Adventures of Billy & Mandy have offered comedic, animated takes on the character.

Theatre, on the other hand, does not have the same affinity for depicting a personified Death. Although many of theatre’s most famous characters die or receive visits from ghosts (see most of Shakespeare’s tragedies), rarely does the figure of Death itself appear on stage. There are a few examples—Death Takes a Holiday is perhaps the most famous, since the 1924 Italian play was later adapted into both a pre-Code Hollywood film and a Maury Yeston musical—but overall, there are far fewer portrayals of Death on stage than there are in film, television, literature, or visual art. In his 2019 book Death in modern theatre: Stages of mortality, scholar Adrian Curtin suggests that this disparity is due to the immediacy and tangibility of theatre:

It is qualitatively different to encounter a personification of death by a human performer in theatre than in a piece of visual art or in a literary work. In the latter cases, ‘Death’ does not have real flesh and blood. ‘Death’ does not breathe. ‘Death’ cannot literally return your gaze if you look at her or him. When ‘Death’ appears before us in theatre, we encounter an uncanny spectacle: a corporealisation of an abstraction – a living, breathing memento mori.

In other words, it may be more disconcerting for us to face a human-like Death when it is physically present, not mediated by editing, brushstrokes, or the inherent distance between a reader and the written word. When Death is on stage, nothing is left up to the imagination.

Although it can be frightening, the practice of personifying and mythologizing Death serves a purpose. It allows us to explain the unexplainable, and make meaning out of what seems meaningless. It is no accident that the famed Grim Reaper representation developed during a devastating plague; death was so sudden and omnipresent at the time that it must have seemed as though an external force was intentionally reaping souls from the Earth in batches, like a farmer harvesting crops from a field. Historians estimate that 45% to 50% of the entire European population died between the years 1347 and 1351. How could one possibly interpret that scale of devastation without a story? The Grim Reaper’s continued prevalence in art and culture is indicative of its utility as a tool for generating meaning. It also explains the many representations of Death from storytelling traditions around the world, like Santa Muerte from Mexican folklore, King Yama from Hindu scriptures, or the demon Mara in the Buddhist religion. Throughout history and across cultures, it has always been comforting to us to be able to explain death, regardless of the accuracy of that explanation. Perhaps we appreciate having an illustration of what happens to our loved ones when they die, or we need a way to explain death to children. Or maybe, in the words of famed theatre practitioner Augusto Boal, we find it useful to create stories about Death as a “rehearsal for the future.”

If the point of a personified Death is to, in effect, rehearse for the death of our loved ones or ourselves, the Grim Reaper doesn’t quite fit the bill anymore. Its imagery is centuries old, and has been so broadly parodied that it is more commonly found in childhood cartoons than in serious artistic considerations of what it means to die. This past year, an anomalous number of lives have been touched by death, and that number will only grow in the months to come. Like late medieval Europeans during the Black Plague, we may be able to help one another process this wide-scale death by creating a Death with a new face, one that more closely aligns with what we think and feel about dying. And if sharing stories about Death is a rehearsal, what better place to debut this new Death than in the theatre?

In Everybody, playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins adapts the 15th century morality play Everyman into an alluring and funny meditation on love, death, and understanding. His adaptation of the character of Death is fitting; in the original Everyman, Death is the archetypical Reaper, a willing servant of God who blindly carries out instructions to reap the soul of Everyman. In Everybody, however, Death is more like a disgruntled administrative assistant who questions God’s orders and engages in honest dialogue with Everybody. In short, Everybody’s Death is human, just like the other characters in the play, or me, or you.

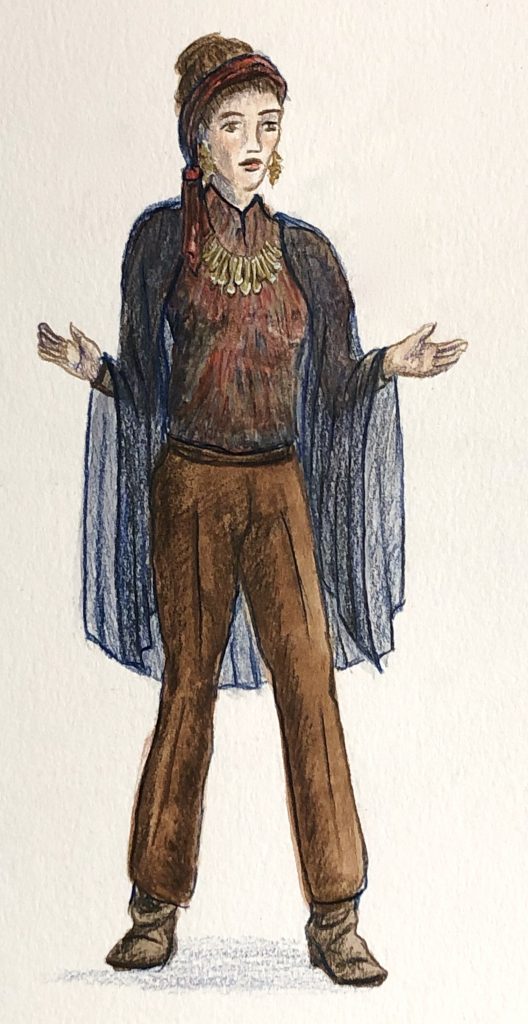

Costume Designers Hannah Brown and Siena Tone took this adaption into account when they began the process of designing Death’s costumes. According to Tone, the team wanted to “steer clear of the typical western depiction of the Grim Reaper” and instead opted for a softer and more colorful Death, with influences from Buddhism and Shintoism. The costumes suit the witty yet sensitive character in the play well; both balance seemingly contradictory traits. Tone explained that “we wanted our Death to have a softness, but with an edge; she is comforting but has a strong intensity.” Death wears hard metal jewelry, but the delicate accordion folds in the cloak mimic the appearance of wings. The colorful palette and gentle silhouettes help to alleviate the “uncanny spectacle” that is the living, breathing Death on screen.

By portraying a fundamentally human Death, Everybody tells a story about dying that is not so much scary as it is humorous and contemplative. When actor Sara Taylor appears on your screen as the exasperated yet approachable Death, a new conception of dying may crystalize for you, perhaps one that feels more useful than the Grim Reaper. By tempering fear with wit, distress with comfort, and tragedy with humanity, Everybody’s Death reminds us that even in its wake, everything will be okay.

Emerson Stage’s production of Everybody by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins and directed by Annie G. Levy opens for LIVE online performances on March 11 and runs through March 14. For more information and tickets, please visit emersonstage.org/everybody.