No One’s Virtuous: Emerson Stage’s New Play Workshop From the Playwright’s Perspective

By: Preslee Krout

A conversation with Greg T. Nanni, playwright of Emerson Stage’s production of RAGE and Emerson student Sabrina Sexauer.

Preslee Krout: Before we begin, please share your preferred name and pronouns if you’re comfortable, your role in the show, a little bit about yourself, and your background in playwriting.

Sabrina Sexauer: My name is Sabrina Sexauer. I prefer the she/her/hers pronouns, and I’m an Acting BFA student. I have been serving as Greg’s assistant, and also as script support; I’ve been kind of sitting back and observing Greg’s process, and what it’s like to be a professional playwright

Greg T. Nanni: Greg T. Nanni, playwright of RAGE, he/him pronouns. How I got started in playwriting? It’s a very long story, so I don’t know how short I can make it. Basically, I went to college for Political Science and English, and I was trying to become a fiction writer. I had a fiction teacher who was like, “I don’t know, you should probably give up.” And I listened to him. Then, I had another teacher at the time who suggested I try playwriting “because of these weird little plays that you’re writing.” But by the time she told me that, I was basically graduated. So, I took a year to just work in the restaurant industry and then decided to move to Philadelphia and started working with Azuka Theater. They took me on as kind of a Swiss Army Knife, if you will, just kind of there to give support in any role. I worked with Sally Ollove there and just wrote plays on the side. Although, I guess it’s funny, because this play actually encapsulates a lot of my life and playwriting career in a weird way.

I was taking a workshop at another company, and it was under John Augustine, and that’s where I wrote a play and John Augustine really liked it, and he’s the husband of Chris Durang. So he was like, “Why don’t I introduce you to Chris and you guys can start talking?” And then my career kind of went all over the place from there. I don’t want to make it sound like Chris Durang launched my career, but it was just like a weird thing that happened while random little doors were opening for me.

PK: So with RAGE, you began it pretty early in your career as a short, and then it developed further into the longer piece?

GTN: Yeah! I wrote it as a 15 minute play, and then I put it away. The scream moment is the only thing that’s really stayed.

SS: Oh! The scream moment!

GTN: Yeah, the silent scream moment. That was an idea that I had, of two people promising they would do something with each other and then not doing it in real life. I just felt that it added to the performative existence that is your online persona. And it’s also kind of my life, too, in a way.

When I was your age, I was super depressed. And I would portray myself as this extremely fun, outgoing, extrovert. I was a clubber. That was a lot of the reason that no one could actually guess what was happening inside my head which was this very dark depression. Basically pretending to be someone, but who you really are is different.

In a way, I guess I related to the idea of Derek and Jaz and how you can stay closer to what your soul wants to say to somebody online, while in person it might be difficult to really communicate with someone.

PK: And how did it evolve from there?

GTN: Yeah. So RAGE was that 15 minute play. Then there was a ten minute play that was produced that was just about the idea of witch burnings. It was during the 2016 election cycle when Hillary Clinton was torn apart completely. I was so interested by the misogynistic, angry action of it. So, I had these two guys who clearly were misogynistic act like they were the victims and then proceed to try to perform a cancel culture move on a politician like Hillary Clinton.

I went to a class at Columbia called American Spectacle, led by Lynn Nottage. In that class she had us visit different theatrical-like events that aren’t theater. So one session you would go to a wrestling match and you would observe how a wrestling match develops dramatically, and analyze the structure of storytelling that wrestlers have. The same thing happens at a megachurch and art installations. Usually, she takes people to a protest or a rally or something like that to see how activists build a story. The megachurch exercise was actually act one of the play.

I’ll have the same two characters, these two people who are lost and are kind of just internet trolls and angry at the world. I’ll have them join this online cult, and see what that looks like. Then as I kept working on it, I was like, oh, this is kind of like that feeling at a megachurch. So, all of the Leveller’s monologues are very much based on the megachurch in that format of the introduction. The lure to get you to come in the group singing or chanting. Then, ultimately, they sing together, chant together, pray together, except it turns into they’re all burning somebody. And I wrote the rest of it in that class where the ideas all melded together.

PK: Amazing! What is your relationship with Rebecca? Especially through the lens of this piece. From what I understand, the two of you kind of developed this piece together and then brought it to Emerson?

GTN: I knew Rebecca from Columbia; I saw a few of her works. She was very movement oriented, which very much attracted me to her because I had a long history of working with an absurdist theater company as a literary manager. When I’m watching directors, I’m looking for how communicable the director is and how they choose to tell stories through their body. So, when you’re looking for a director who can support that, you’re looking at how well they can communicate without language. And I thought that Rebecca was just extremely strong at it. So when I finished the draft of RAGE, I talked to Rebecca and we did a reading. We kept talking about it. And then we did a second reading of it in David Henry Hwang’s class.

So we were always in conversation about the piece, and I was like, “I’d love to do this with you one day.” I finished the play and we were in discussion about it, and it had three readings, and then Covid slowed everything down. And when this opportunity came up, Rebecca was like, “Why not? Let’s see what happens.”

PK: That leads into my next question, which is, how has the workshop process for the NewFest at Emerson differed from other workshops that you’ve done?

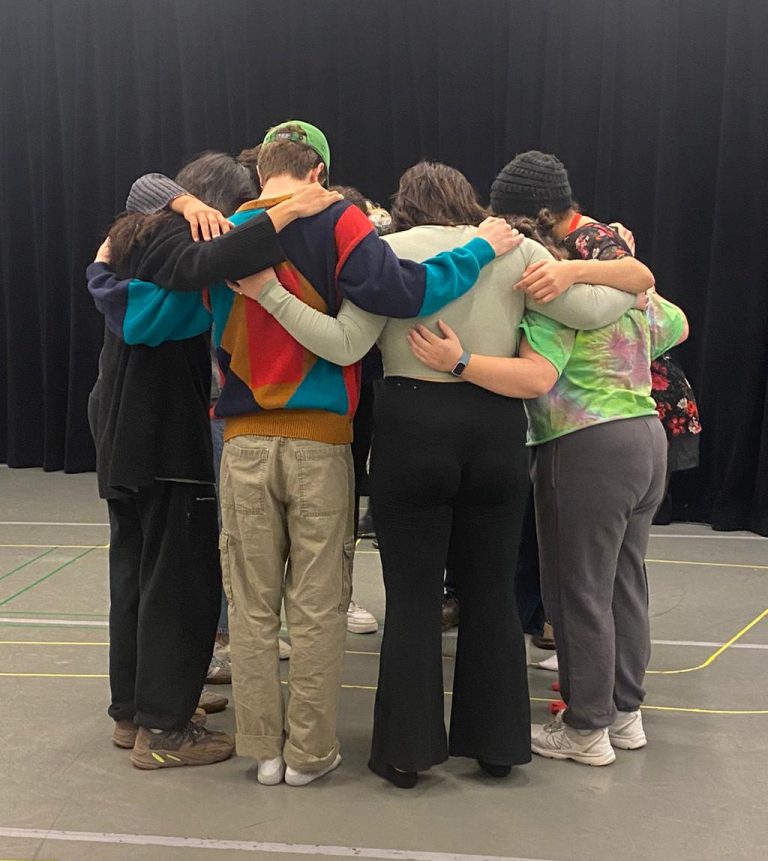

GTN: The level of enthusiasm at Emerson College has been like…crazy. They’re very excited about the work. They’re trying all these different approaches. They’re doing their damnedest. And it’s really rewarding to watch that. I would say some of the big differences in Emerson versus other workshop opportunities I’ve had in the past is the level of support at Emerson College is amazing. I mean, I have you two. There are all these students working on this production and that is so amazing and rare. The support level here is just phenomenal. Rebecca and I feel so spoiled by this because we’re just like, “Wow, these people are so amazing, and these students really give a shit.”

PK: I’m so glad your experience has been positive!

SS: Adding to that: watching how Greg and Rebecca treat Emerson students throughout the workshop process was awesome! We did three whole days of table work. Everyone had so many questions and was just ready to lovingly challenge and figure out everything about the play. And I feel like everyone brings that zeal into the creative process. Everyone wants to dive a layer deeper. Greg and Rebecca are so responsive to hearing other people’s suggestions, and that was something that I was really surprised by. I think Preslee, both you and I, we’ve probably made suggestions that, Greg, you’ve either heard out or incorporated into the script…which is insane. I know I feel super respected as a contributor.

My favorite thing that you’ve said, Greg, this is something that I’m definitely going to bring with me, is that at a certain point the playwright’s job is to listen to everyone’s suggestions, take in what everyone has to say, and then decide what things to listen to or what things to politely pass from, in service to the story.

I hate to get super existential with it, but there’s all these discussions about how to make theater more accessible, and how to challenge the power structures that make theater so inaccessible. I think one of the things that I keep on hearing time and time again is dismantling that idea of some people being up here, just some people being down here. Some people are legends beyond touch or beyond approach. As much as we love Billy Shakes, Billy Shakes is not the be all and end all.

PK: Oh, this is great. That gets into my next question: Sabrina, how have you been able to take your perspective as a playwright, especially from Emerson? I feel like it’s a very specific kind of community to be creating art in.

SS: I think off the bat, this is a very interesting play to bring to Emerson. The subject matter is uncomfortable. It’s one of those things that if you were to describe it at face value, I think the typical Emersonian might be a little turned off at first. I feel a little scared or vulnerable saying this…You could write a morally dubious character and people automatically link the morally dubious character to the writer’s own moral compass. I’ve seen this at Emerson; I’ve had it happen to me. I can’t say that it’s just Emerson. I think it’s our generation and how we approach art as a whole. I think it stems from us wanting to be more socially conscious, and I think that’s really important. However, I think we can be socially conscious and also be a little bit more analytical at the same time.

GTN: No one’s virtuous. So it’s strange to apply a level of virtuosic expectations on people ubiquitously when people naturally grow from their inherent contradictions, their inherited habits, and their inherited traumas. People just have so much within them that I think it’s always like a rolling storm. And some people let that out through being able to talk with others really well, some people let it out through their work.

This is a play about people that can’t let it out. When you can’t express yourself, when you can’t talk about things like depression, or a static class system, when you’re so frustrated at who you’ve become in this world that you kind of enjoy taking it out on others online behind these anonymous masks that we wear. No matter what, your characters are egos into themselves, are self conflicting and self destructive.

When working on this play, a big goal of mine was to make it more about class. I took a lot of feedback the students were having about material that was difficult. I was interested in finding the right ways to still have this level of discomfort and difficulty of what you’re watching, but perhaps not have things be as visceral. I think the main influence from this process with Emerson students is just hearing about what interests you in the script to kind of see how it works with people that are ten years younger than me. What speaks to you? What feels a little bit outdated? It’s even fun when something’s cheesy and it’s like, oh, how can I amp that up?

SS: Right, the moon! The moon scene!

GTN: Yeah, the moon section! With that section, I always worked with older actors and they never brought anything up. Then watching the Emerson students tackle it, I was like, “Oh, yeah, it’s really awkward. Oh, let’s amp that up.” Ultimately in a workshop, you’re in a nebula of minds and you’re finally hearing your words echo back.

PK: I have one more little question, and Sabrina you sort of already answered it. What are you most looking forward to in showing it to an audience?

GTN: So that’s actually where the work continues for me. I’ll probably be sitting there every night with the script and mark when people are leaning in and when people are leaning out. It’s just based on the energy that you feel in the room. Whenever you can tell someone’s engaged or whenever they’re kind of like zoning out. We’ve been working on this story since November, so it’s going to be very interesting to see what the reaction is to the product with people who aren’t in the tunnel of the world that we built together. That’s going to be extremely informative. I’m going to be looking for that cringe. I want to see where that cringe is. I feel like the play is both more brutal and less cringe worthy now. So it’s going to be very interesting to kind of watch it from that perspective. That’s the most rewarding time as a playwright.

PK: That’s great. Sabrina? The moon scene?

SS: Moon scene. That’s all I have to say about that.

GTN: I think it’s going to be a lot of fun. I’m jumping out of my seat to see it all come together.

Emerson Stage’s NewFest 2022 New Play Workshop of RAGE by Greg T. Nanni and directed by Rebecca Miller Kratzer opens to the public on Sunday, February 27 at 2 p.m. EST and runs through March 2 at 8 p.m. EST. More information and tickets are available at emersonstage.org/new-play-workshop-2022.